The 24th of April marked the 105th anniversary of the commemoration of the Armenian Genocide, when the Ottoman government implemented the organized extermination of the Armenian people living in Turkey at the time, carrying out mass deportations and killing an approximate 1 – 1.5 million Armenians between 1914-1916. Although the COVID-19 pandemic meant that the customary commemoration services could not take place this year, people were invited to commemorate in other ways, including virtually visiting the memorial in Yerevan, Armenia (Asbarez Staff, 2020).

In the decades since this genocide, the discourse among survivors and their descendants has included a focus on remembering the facts of the events and demanding recognition of the genocide by Turkey and by powerful third parties such as the United States. Indeed, one of the key needs of victims in the aftermath of genocide is acknowledgement. But contested facts over what exactly constitutes acknowledgement and over the account of events by both victim and perpetrator groups mean that acknowledgement itself is complex (Vollhardt & Twali, 2019). In our own research on political apologies, we examine the contents of apologetic discourse and people’s evaluations of these ‘statements of acknowledgment and expressions of remorse’. Interestingly, on the eve of the 99th anniversary of the commemoration of the Genocide, then Prime Minister Erdogan offered his condolences to the families of the Armenians who had “lost their lives” (“The unofficial translation”, 2014). His statement prompted mixed reactions from Armenians around the world (Letsch, 2014). As an academic who studies apologies, I regard Mr. Erdogan’s statement as a non-apology. It falls short of the kind of statement that could be accepted by most descendants of Armenian victims.

First, Mr. Erdogan did not acknowledge the wrongdoing. He referred to the transgression of genocide as “the events of 1915”, later stating that millions of people lost their lives in the First World War which resulted in inhumane consequences such as relocation. By situating the Genocide in the context of the First World War, Mr. Erdogan avoided making any real reference to genocide. He portrayed the genocide as an inevitable and uncontrollable consequence of the war. Second, Mr. Erdogan made what some would regard as a statement of remorse: “we wish that the Armenians who lost their lives in the context of the early twentieth century rest in peace, and we convey our condolences to their grandchildren”. This seems conciliatory, but is indirect and somewhat implicit in meaning. By offering condolences, Mr. Erdogan evaded taking any further responsibility. Without the context of explicit acknowledgement and direct acceptance of responsibility for genocide, his words are perceived as insincere and shallow. Third, Mr. Erdogan did express a recognition of Armenian suffering (“It is a duty of humanity to acknowledge that Armenians remember the suffering experienced in that period”). However, this sentence was immediately followed by “…just like every other citizen of the Ottoman Empire”. Elsewhere, he referred to the suffering of many, shifting the blame from the Turkish powers to an inclusive construal of framing: “Any conscientious, fair and humanistic approach to these issues requires an understanding of all the sufferings endured in this period, without discriminating as to religion or ethnicity”. This type of framing (when done by the perpetrator group) consequently avoids responsibility and detracts from the victims’ suffering (Vollhardt & Twali, 2019).

Turkey has an unhidden history of denying the genocide and her involvement in it (Balakian, 2005). Mr. Erdogan may not have explicitly denied the genocide in this particular statement, but his rhetoric conveyed a message in line with the culture of denial. For victims and survivors of genocide, denial is a continuation of the genocidal process (Stanton, 2016). Mr. Erdogan’s statement reiterates the complexities of how apologetic discourse is constructed and can be used to avoid acknowledgment and perpetuate denial.

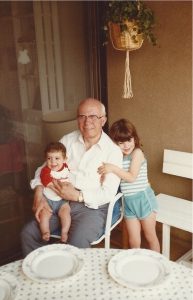

Studying the Armenian Genocide and its aftermath is more than an exercise of academic and moral concern for me. My paternal grandfather and my paternal grandmother’s parents were survivors of this genocide. I grew up in a community where – if asked ‘Where are you from?’ – one gave the name of the historical Armenian town in modern-day Turkey from which their family had been deported. My grandfather’s village was Hasanbeyli. One afternoon, he told me his story: how he, along with his mother and brother were deported from their home; how they were forced to walk in the desert until they eventually reached Aleppo; and how his mother found creative ways to feed her young children when there was no food source. I was ten years old at the time, but I recognized the weight of my grandfather’s words. It was a personal testimony, the witness of one whose story has been multiplied a million times over.

Thia Sagherian-Dickey

Balakian, P. (2005). The burning Tigress: A history of the Armenian Genocide. London: Pimlico.

Letsch, C. (2014, April 23). Turkish PM offers condolences over 1915 Armenian massacre. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/23/turkey-erdogan-condolences-armenian-massacre

Asbarez Staff (2020, April 23). Make a virtual pilgrimage. Asbarez. Retrieved from http://asbarez.com/193773/make-a-virtual-pilgrimage-to-dzidzernagapert/

Stanton, G. (2016). 10 stages of genocide. Genocide Watch. Retrieved from http://genocidewatch.net/genocide-2/8-stages-of-genocide/ .

The unofficial translation of the message of H.E. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the then Prime Minister of the Republic of Turkey, on the events of 1915 (2014, April 23). http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkish-prime-minister-mr_-recep-tayyip-erdoğan-published-a-message-on-the-events-of-1915_-23-april-2014.en.mfa

Vollhardt, J. R., & Twali, M. S. (2019). The Aftermath of Genocide. In L. S. Newman (Ed.), Confronting humanity at its worst: Social psychological perspectives on genocide (pp. 249–283). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190685942.003.0010